- Home

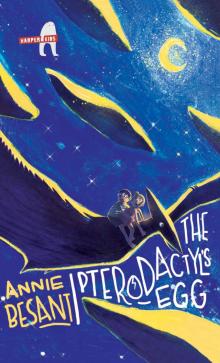

- Annie Besant

The Pterodactyl's Egg

The Pterodactyl's Egg Read online

For

Sam, the boy who wanted a dinosaur story

and

John, for inspiring me every day.

Contents

1. Lost and Found

2. Pencils and Privates

3. A Tap-tap in the Night

4. A Bird Is Born … Err …Or a Reptile

5. Poongothai

6. Mom in the Middle

7. Bringing in BENO

8. The Gender Debate

9. How to Train Your Pterodactyl

10. A Night Flight

11. Facing the Enemy

12. Betrayed!

13. Oh, Brother!

14. Settling Scores

15. Wonder Mom

16. Letting Go

17. A Boat, a Boy and the Wrath of Dr POX

About the Author

Copyright

1

Lost and Found

Sam kept his head down and walked straight to the sandpit. He hated playing in the sandpit with the babies. But he couldn’t play anywhere else in the park. The bigger and older kids took the best spots, the best slides and the best swings. They pushed and shoved anyone who got in the way.

So Sam sadly sat in the sandpit and half-heartedly built castles. At least the sandpit had been filled with new sand just that morning. He dug and dug and dug when suddenly his plastic shovel hit something hard. Sam peered at the object through his glasses, which were as thick as glass bottle bottoms.

Was it a rock? Sam cleared the sand from around it and dug it out. It wasn’t a rock, but it was shaped like an egg and slightly rough and felt leathery. Curious, Sam shook it. There was no sound. Sam suddenly had a thought. He had seen an egg exactly like this one on TV a few evenings ago. The egg he had seen was a fossil, a dinosaur’s egg! Sam gasped. He had found a dinosaur’s egg.

He looked around quickly to make sure no one was watching. He slipped the egg into his t-shirt, picked up his plastic shovel and swiftly walked back to his apartment block.

He didn’t stop to pet the street dogs like he usually did or say hello to the old watchman or even to admire his neighbour’s Jupiter X100 mountain bike. If his mother had been watching, this last thing would have surprised her. Ever since Sam’s friend Arjun had received the bike for his birthday, Sam had spent many hours gazing longingly at it.

But Sam was too excited with his find to stop for anything. He rushed home and, after making sure he had scraped the sand off his shoes, he snuck into the living room.

‘Sam, is that you?’ his mother called from the kitchen.

Sam groaned. His mother had the ears of a bat. He suddenly pictured his mother as a bat and laughed.

‘Sam!’ his mother called again.

‘It’s me, Mom,’ Sam yelled back before hurrying to his room.

Sam’s mother sighed when she heard the door shut loudly. He had missed lunch.

Sam rushed to his desk and gently took the egg out from underneath his t-shirt. Grains of sand still clung to it and he wiped them away with a towel from the laundry basket. Sam placed the egg gingerly on his desk and grabbed a book from his shelf: All You Need to Know About Dinosaurs by Professor Zao Zatziki.

Sam rifled through the pages urgently, silently apologizing to the book for his haste. He glanced over at the egg; he vaguely remembered seeing something similar in the book. He found it on page forty-seven.

Torvosaurus Egg

The Torvosaurus was a massive bipedal dinosaur. It grew up to 36 feet in height, but laid eggs that were about 6 inches in diameter. The eggs are spherical.

Sam eyed the egg on the table doubtfully. It didn’t exactly match the picture of the torvosaurus egg in the book.

‘But it has been buried for so long,’ Sam reasoned with himself. ‘Maybe that’s why it doesn’t look the same.’

He put the book aside and reached for another book on dinosaurs. Sam was the sort of boy who had more than one book on dinosaurs. In fact, he had read this one so many times that its spine was broken.

He settled down to read it when his mother knocked on the door.

‘Sam,’ she said. ‘Come and eat your lunch.’

‘Not hungry,’ Sam replied loudly, running his finger down the index.

He had just found torvosaurus when his mother’s reply came, ‘Come to lunch right now or there will be no reading hour tonight.’

Sam frowned. His mother was so bossy! But he knew her well enough to know that she would carry out her threat if he didn’t eat.

So he did what any sensible nine-year-old would do: he opened the door, marched to the table, gulped down his lunch in a record two minutes – his stopwatch was running – and then rushed back to his room.

2

Pencils and Privates

Dr POX sharpened a pencil and tested its point. Satisfied, she laid it next to the fifteen other pencils that she had sharpened in the last fifteen minutes. She had just picked up the sixteenth pencil when there was a knock at the door.

‘Enter,’ she said, sitting up straight in her chair and laying the sixteenth unsharpened pencil at a perfect right angle to the others.

A thin, nervous man in grey uniform rushed into the room.

Dr POX frowned. She didn’t like haste of any kind. Clearly the boy had not been under her command for very long.

‘Attention, Private!’ Dr POX barked.

‘Yes sir,’ the man said sharply, saluting her. ‘Err … ma’am.’ Then, seeing her face tighten, he said, ‘I mean sir.’

‘Dr POX will do,’ she said with a very mild trace of anger in her voice. There was much she was going to have to teach this boy. ‘Report.’

The private gulped. They had played rock-paper-scissors in the security centre as soon as the interrogation was over. He had been cut once and smashed twice, and so here he was in the dragon’s den, preparing to give her the bad news.

‘We … ahh … we –’ the private stammered.

‘Look here, boy,’ Dr POX said, calmly picking up a sharpened pencil and feeling its point. ‘I expect nothing more than a cow’s intelligence from you. However, if you insist on it, I could treat you the way I would treat a single-celled amoeba.’

The private’s eyes bulged and his throat worked furiously. She was pointing the pencil at him quite casually, but it was now or never. If he didn’t blurt out his message, he would be skewered.

‘We don’t know where he sent it,’ he blurted out. ‘He refused to tell us.’

‘He refused to tell us?’ Dr POX mimicked. Then she shook her head, sighing sadly. ‘Why do I have to do all the work around here? Isn’t it enough that I have to run this facility, monitor the research and take care of you imbeciles? Do I have to do the interrogation myself too?’

The private’s throat went dry.

‘Get out,’ Dr POX hissed.

His heart flipped, relieved that he had escaped with nothing more than sarcasm thrown at him.

He backed away and was turning to the door when she said, ‘I will deal with you later.’

The private ran out of the office and shut the door behind him. He realized with deep embarrassment that he had peed in his pants.

Six hours later, Dr POX sat down at her desk to continue sharpening the sixteenth pencil. She was satisfied and angry at the same time. She knew the chain of events, she knew what her next step was going to be, but she was furious that the disaster had happened in the first place.

Dr POX and her associates had spent billions of dollars on their research. They had spent several more on misdirecting the government about their true purpose and buying the land for their research facility right from under the noses of the tribes who had once called it home.

Dr POX snorted. Home. She was working on what w

ould be the greatest revolution in the history of mankind. She was going to put the likes of Copernicus, Newton and Darwin to shame, and all these people could think about was their home.

Sighing, she put the pencil next to the rest. She had a long night ahead of her with calls to make and e-mails to send. They had to find the truck within the next twenty-four hours. Her research, no, her life depended on it. It depended on a single egg; an egg that had found its way out of her hands due to human greed.

3

A Tap-tap in the Night

Sam tossed about in his bed. His eyes hurt from having stayed up late reading by the light of a candle (thanks to the power cut). It had then developed into a headache that left him sleepless. He thought about knocking on his parents’ door and asking for a tablet, but that meant he would have to explain to his mom exactly why he had a headache in the first place. It meant he would have to tell her that he had read past his scheduled reading hour. It meant he would have to tell her why he was reading beyond his scheduled reading hour. It would lead to his mother getting angry. And if he didn’t want his mother to get angry – and he really didn’t want that – he couldn’t ask for a tablet and he was stuck with this headache.

Sam pushed his head deeper under the pillow as if by burying his head he could forget it existed.

‘Maybe that is why dinosaurs buried their eggs,’ Sam thought, ‘so that they could forget about them.’

The thought reminded Sam of the egg. Was it really a dinosaur’s egg?

Sam yawned. He was beginning to feel sleepy. He grunted and yawned again when he heard it – a light tap-tap – as if someone was drumming their finger on a table.

Sam went still. The tap-tap was followed by long minutes of silence. All he could hear were the ticking of the clock and the lathi sounds of the security guard who patrolled their colony.

He rubbed his eyes and yawned again.

Tap-tap.

He froze. He had heard it again! He heard it every time he yawned. Sam brought his head out from under the pillows and searched for his glasses.

He couldn’t help letting out an enormous yawn.

Tap-tap-tap.

Sam got his legs tangled in the sheet and fell off the bed in his rush to find his glasses. They weren’t on the bed or on the bedside table. He frantically tried to remember where he had left them. The tap-tapping sounded again, this time urgent and loud.

‘The book! I left it on the book!’ Sam yelled to himself silently. He scrambled to his feet and ran to the table, knocking down his dinosaur toys, pens and building models in an effort to get to his glasses.

His elbow knocked the egg, which he had forgotten was still perched on the table, and it fell to the floor with a thud. Sam didn’t care. He simply had to find his glasses. He finally found them tucked into his dinosaur book like a reluctant bookmark.

Sam put them on, pushed the hair out of his eyes and looked around. The sound had stopped.

He strained his ears, but all was silent again except for the ticking of the clock. He suddenly felt foolish. He had always been scared of the dark. Maybe he had imagined the whole thing.

Sam sighed and then shrugged. His head was pounding again, as if someone was playing the drums and his head was the stage.

‘Stupid head,’ Sam muttered, shuffling to his bed, when he heard the sound again.

This time, the tap-tap sounded like someone knocking urgently on a closed bathroom door. Sam listened carefully, turning his head this way and that. He gulped when he realized where the sound was coming from.

Sam went back to the table and knelt down. He bent close to the egg just as a crack appeared in the shell. Sam reached out gingerly to trace the crack; the door to his room opened and his mom appeared in the doorway.

4

A Bird Is Born … Err … Or a Reptile

Sam fell on his bum as he tried to shield the egg from his mom and climb to his feet at the same time.

‘Sam,’ she said, ‘What are you doing?’

‘Priya!’ Sam gasped in relief. ‘Thank god. I thought you were Mom.’

For a moment, his sister looked like she didn’t know if that was a good thing or a bad thing. ‘What are you doing?’ she asked again, her head cocked to the side like a curious cockatoo.

‘I … nothing,’ Sam said, planting himself in front of the egg.

‘You were doing something,’ his sister said suspiciously. ‘I heard you bumbling about like a platypus.’

Sam retorted, ‘I don’t think a platypus bumbles.’

‘Whatever,’ his sister said, waving her hand. ‘What are you doing?’

Sam groaned. His sister was as stubborn as a pit bull. He had once seen a TV show where a pit bull got hold of a bone and wouldn’t let go.

‘Were you reading again?’ Priya asked when her brother remained silent.

‘Yes, yes,’ Sam said, grasping at the excuse with both hands. ‘But I was going to go to bed.’ Then, as if a thought struck him, he asked, ‘What are you doing up so late?’

It was interesting to watch his sister’s face go from suspicious to defensive. ‘Nothing,’ she snapped. ‘I was getting some water to drink.’

Sam shook his head. ‘Mom always leaves water in the room for us in case we get thirsty at night. You were talking on your phone, weren’t you?’

Priya put her hands on her hips. ‘That is none of your business, platypus,’ she huffed. Sam grinned and Priya eyed him suspiciously. Her brother was getting too cheeky. Then, she shrugged. ‘Better go to bed, platypus, or I will tell Dad and Mom you were up late.’

Sam released his breath as she turned to leave. ‘Yes!’ he did a jig in his head. The egg, however, had other ideas.

Priya was thinking of all the ways she could torture her brother the next day when she heard it.

Tap-tap.

‘What is that sound?’ she asked, turning back to her brother.

‘Nothing,’ he said quickly, too quickly. ‘Just me, tapping on the floor.’ He proceeded to demonstrate how well he could drum the floor with his fingers when the egg cracked with a sound as loud as a coconut being cracked on a rock.

Seconds later, they heard a hoarse shriek, like a fledgling crow crying for food.

Sam gasped and turned to the egg behind him. Priya hurried into the room and stood next to her brother.

She too gasped when she saw what she saw.

Priya and Sam turned to each other; their eyes were round ‘O’s in their faces.

They turned and stared at the egg before staring at each other again.

‘What. Is. That?’ Priya asked.

Sam cleared his throat. ‘I don’t know, but I think … I think, Priya … that –’

‘What do you think, platypus?’ Priya exclaimed.

‘I think,’ Sam said, clearing his throat, ‘that … that is a pterodactyl.’

5

Poongothai

Dr POX liked to boast that she was a product of science. When her parents had given up all hope of having a child, science had intervened and delivered.

When this truth was told to her at the age of nine, Dr POX was fascinated. Unknown to everyone, she was a child genius with a mind that could swallow science journals, encyclopaedias and research papers whole. In fact, her own schoolbooks bored her to tears.

By the time she was twelve, she was designing lab equipment for top research companies, building science instruments that made her teachers sweat and constructing scientific theories like the ones that had made Albert Einstein’s hair stand up. But instead of sitting up and taking notice, Dr POX’s parents began to worry.

They knew their daughter was different, but the degree of her difference from other girls made them worry. When an aunt gifted her a doll house for her tenth birthday, Dr POX had set fire to it and made sure not a single doll survived. On her eleventh birthday, she had applied for a MENSA membership without her parents’ knowledge; and on her thirteenth birthday, she had used her school scholarship money to

build herself a science lab from scratch. But instead of flaunting their daughter as a prodigy to anyone who would listen, they began to send her to counselling sessions.

Dr POX’s counsellor, fresh out of college with a shiny new degree, assured the young girl that something was wrong with her love for learning, her experiments, her ideas, right down to her personality. Sixteen sessions later, Dr POX’s parents were delighted to find that their daughter was now just another girl. What they didn’t know was that during the fifteen sessions, Dr POX had learnt an important truth: no one liked anyone who was smarter than them.

She first tested the theory by going along with the counsellor’s assessment of her personality. The counsellor, who had found her every word irritating, now found that his patient was humble and willing to listen. This not only changed his personal opinion of her, he went as far as to tell her that maybe she ‘wasn’t so bad after all’.

In their sixteenth session, he told her parents that she was perfectly normal and didn’t need his help anymore. Everyone rejoiced, and sixteen became Dr POX’s favourite number because that was when she had finally learned to fool the world.

Years later, Dr POX graduated from a top university in America – she had told her parents she was studying history when actually she was mastering molecular biology and genetics. Dr POX went on to work under Nobel Prize winners and top geneticists (her parents happily told their neighbours that their daughter was a teacher in a primary school).

However, here too Dr POX discovered that no one liked anyone who was smarter than them. Colleagues stole her ideas and bosses sent her research papers to top journals under their own names. Years later, as Dr POX sat sharpening her pencils, she would imagine their faces on each of the pencils that she put through the sharpener.

Soon, Dr POX stopped talking to the people around her. She thought bitterly that she now understood why geniuses died so young – the world around them was enough to drive them mad. And so, to keep herself from going mad and dying young, Dr POX thought about getting a hobby.

The Pterodactyl's Egg

The Pterodactyl's Egg